What to call the keys, or -Which C is that one over there? by Kendall Ross Bean

This is a Print Friendly Version Only. For original article with full navigation Click Here

There are several places where references are made to c(1), C(2), etc. The (1) would normally be written as a superscript (slightly above the height of the C) but, because some browsers will garble the text when we use the superscript, we have put superscripts in () instead

A problem often arises from the fact that on the piano keyboard there are several different C"s, D"s, A"s, etc. What do you call the C two octaves below middle C? --Or the one two octaves above? How about the A at the bottom of the keyboard? Over the many years since the invention of keyboard instruments, there have been several systems devised to specify which note is being referred to. Alas, each method has its drawbacks. And since there are at least 3 or more of these systems in general use today, it can get quite confusing, since the systems often use the same names to refer to different keys.

When children (or adults) start out learning the names and locations of the notes on the piano, they usually start with middle C and its immediate neighbors (that C being the most convenient one, directly in front of the player and usually very close to, or underneath, the nameplate of the piano near the middle of the keyboard. If the name is short, like on our fabulous Steinbald piano example below, middle C may actually be slightly to the left of the name. )

As beginning piano students gradually work their way up and down from this reference point, they also get to know the keys towards the extremes of the keyboard. But still, both children and adults often confuse the C's above and below for middle C. They also frequently get mixed up about which octave A, D, F, G, E or B they should be playing. Even piano tuners sometimes get lost. It should be easy enough to remember that Middle C is right next to or under the piano name, but lots of folks still forget. Many times, too, pianos get refinished, and the name doesn't always get put back on the fallboard; or else it gets rubbed off after many years of playing.

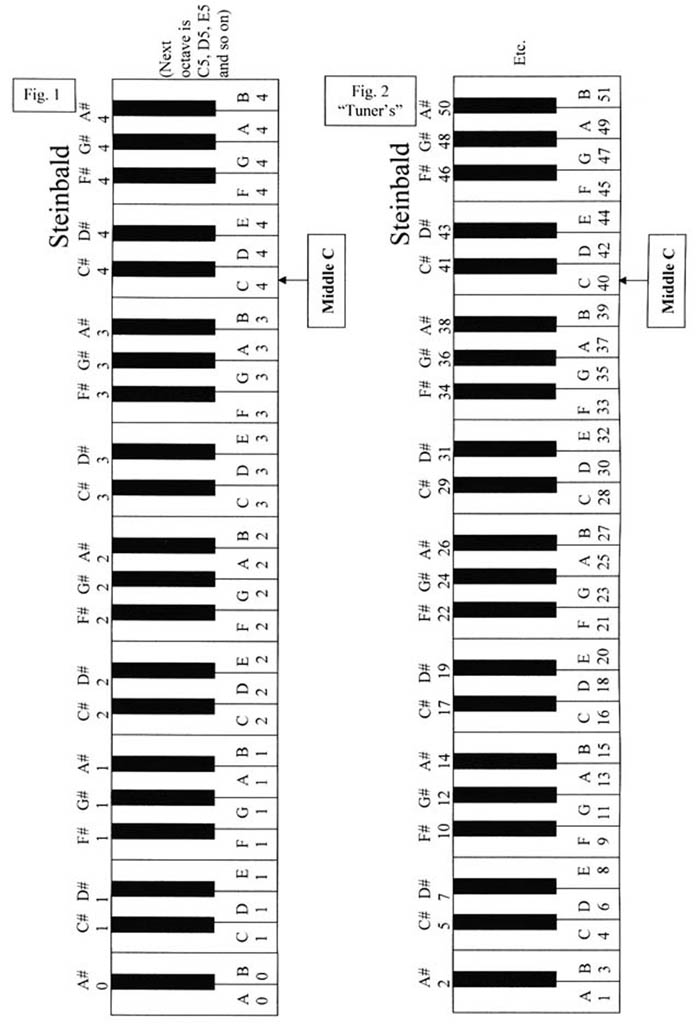

In one system that has been around since anyone can remember, the notes are numbered according to the octave in which they lie, and each new octave starts with C (not A as you might expect). (Figure 1, below. Please excuse that I wasn"t able to fit the full keyboard on the page. Hopefully you will be able to fill in the remaining (upper) part of the keyboard yourself.) Thus, the first C at the far left of the keyboard is C-1, the next C an octave up is C-2, then C-3, C-4, C-5 etc on up to C-8 at the top of the keyboard. Because each octave begins on C, the notes to the left of (or below) C-1 are labeled A-0 (A-zero), A#-0, and B-0 (here we run again into that same problem common in music, not starting with "A" in the first place). Although confusing, this system has been used for many years, and many musicians and piano tuners still use it today. In this system, middle C on the keyboard is C-4. This "C/octave numbering" system was probably instituted at a time long ago when keyboards had fewer keys and started at C-1, before the last three notes were added at the bottom of the keyboard.

There are numerous reasons why there have been so many key numbering or labeling systems throughout history. Part of the problem stems from the fact that the piano keyboard has not always had 88 keys. As a matter of fact, since the time of its invention the piano keyboard has started and ended on a number of different keys. Early pianos had "short" keyboards, with only four to six octaves, just like most organs and electronic keyboards still do today. (Except at the time they were not considered short.) Keys at each end of the keyboard that we take for granted on the modern piano did not even exist yet on many early pianos. As the compass of the keyboard has expanded at both ends, new systems had to be evolved; and because people are reluctant to give up what they have spent time learning, many of the older systems still persist in one form or another. Currently there does not seem to be any universally accepted system that accommodates both long and short keyboards.

In attempting to find a system that can accommodate future expansion of the keyboard, it"s important to recognize the principle that the piano keyboard really "started in the middle and grew outward". Piano makers added keys at each end of the piano keyboard as composers and musicians demanded more range. Based on this, some key labeling systems try to do the same, and work their way outward from the middle; from the familiar, to the less familiar. (This is probably another reason why we still have ledger lines for the highest and lowest notes, and why people still have trouble learning or reading them.)

Singers and instrumentalists often have their own unique systems for what to call the notes. A singer might refer to the 6(th) C (C-6 according to the above system) as "high C". But then, if high C is two octaves above Middle C, what do you call the C one octave above? Which is low C? You can "C" why this is also confusing, especially to non-singers.

Some musicians try to get by, by relating everything to middle C. (As in: "Play the G an octave below middle C, please.") However, having to refer everything to middle C is cumbersome at best: some notes at the far ends of the keyboard are a long ways from Middle C and, just like with driving in a strange city, you can get lost trying to follow directions. Some instrumentalists and singers are not familiar with keyboards, so to them, Middle C might not have much significance. Using middle C as a reference point might, however, be one way to communicate if you frequently work with keyboard musicians who use keyboards or synths that have only 61 or 76 notes, but who do know where Middle C is.

A second system, used currently by piano tuners, numbers the keys on the piano from 1 to 88. (See Figure 2) Hence A-1 is at the bottom of the keyboard, and C-88 at the top. This works well for 88-key pianos, but as we said, many keyboards on organs, synthesizers, and electronic pianos are shorter than 88 keys, so unless one remembers that Middle C is C-40, and unless one can count both downwards and upwards from C easily, this system becomes confusing as well. This second system was really only adopted when pianos began being standardized at 88 keys. In the diagram you will see that each note on the keyboard has a number from 1 to 88, counting up from the left (or bottom end) of the keyboard, and including the black keys.

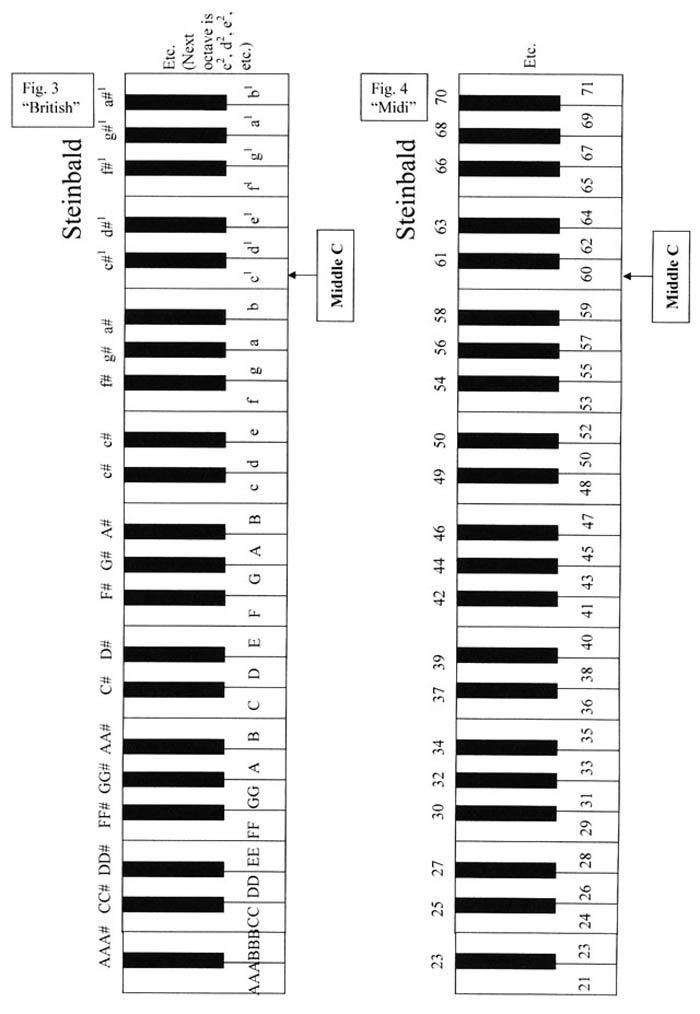

There is a third system that was or is evidently used in the British Isles, described in David Crombie"s landmark book "Piano" (1995, Miller/Freeman, San Francisco) as the "standard reference system." This system actually does start in the middle, with Middle C as c(1), and, just as in the first system described above, each new octave begins on c. The octaves above middle C become c(2), c(3), c(4) and, at the top of the 88 note keyboard, c(5). The notes below c(1) do not have numbers associated with them, but are differentiated by either being lower case (a, b, or c), upper case (A, B, C) or double (AA, BB, CC) or triple (AAA, BBB) upper case. See Figure 3. This is somewhat similar to a system used in the Encyclopedia Britannica (1981) in their section on Keyboard Instruments, the difference being that the Britannica labels the C"s, starting with Middle C and going upwards, as c', c'', c''', c'''', and c''''' at the very top. From Middle C downward, according to Brittanica, is c", c, C(1), C(2), which bears some resemblance to the system in Crombie"s book as well (c(1), c, C, CC). However, Brittanica then proceeds to muddy up the waters again by saying that the note at the bottom of the keyboard is A2, as opposed to AAA in Crombie. In addition, Brittanica feels the need to use the terms high C and low C to further explain what they mean. In their system, high C is two octaves above Middle C and low C an octave below. But that still leaves us in suspense: what to call that elusive C an octave above Middle C? Note that, even in these two systems, C1(c(1)) and C2 (c(2)) mean different things.

To add more fuel to the controversy, another source I consulted, on Introductory Music, calls the c an octave above Middle C "high C". Thus we have at least two different c"s, one two octaves and the other one octave above Middle C both being referred to as "high".

With the advent of MIDI, the Musical Instrument Digital Interface designed to hook electronic and acoustic pianos, synthesizers, samplers, and other types of keyboards together, there is still another system (Figure 4). The MIDI system specifies Middle C as note # 60, and then works downward and upward from there. In the MIDI specification, as a result of binary language (7-bit words, or 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2), there are 128 notes possible, so it was evidentally decided to extend the range far above and below that of the standard 88 key keyboard. This will, no doubt, bring yet one more element of confusion to the problems of what to call the keys on the piano.